Twenty–five years ago, I wrote ‘Glimpse Back at a Future City’, a 30-year look at Expo 70. Now, at the 55-year mark, that event still crackles with relevance. In 1970, under the banner ‘Progress and Harmony for Mankind’, 64 million people streamed into Suita to inspect moon rocks, robot hosts and the Tower of the Sun, or perhaps just people’s backs.

Expo 2025 on Yumeshima offers a softer, digital vision. Opening April 13th, 2025 and running for 184 days, it invites 28 million guests to shape ‘Designing Future Society for Our Lives’ in a ‘People’s Living Lab’ dotted with biomaterial pavilions and Sou Fujimoto’s two-kilometre Grand Ring.

Apparently, there are also tea and scones.

Once again, Osaka sets itself a test of reinvention on a stage ringed by sea walls. Where 1970 celebrated the machine, 2025 promises data-driven care, carbon-negative timber and avatars that speak every language. The question remains: can a World Expo still bend the arc of urban possibility?

Next week this column runs the numbers: we revisit Expo 70’s jet-pack dreams, tally what came true, and assess whether Yumeshima’s biotech and flying-car promises are destined for reality or relegation to nostalgia.

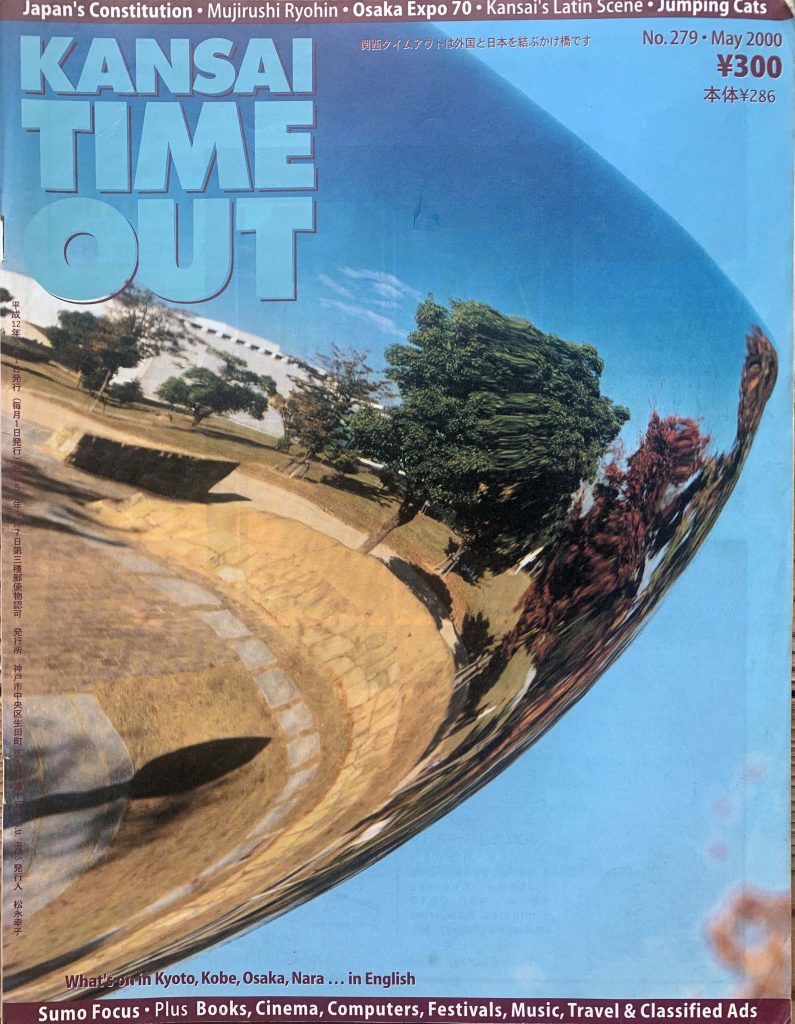

Glimpse Back at a Future City

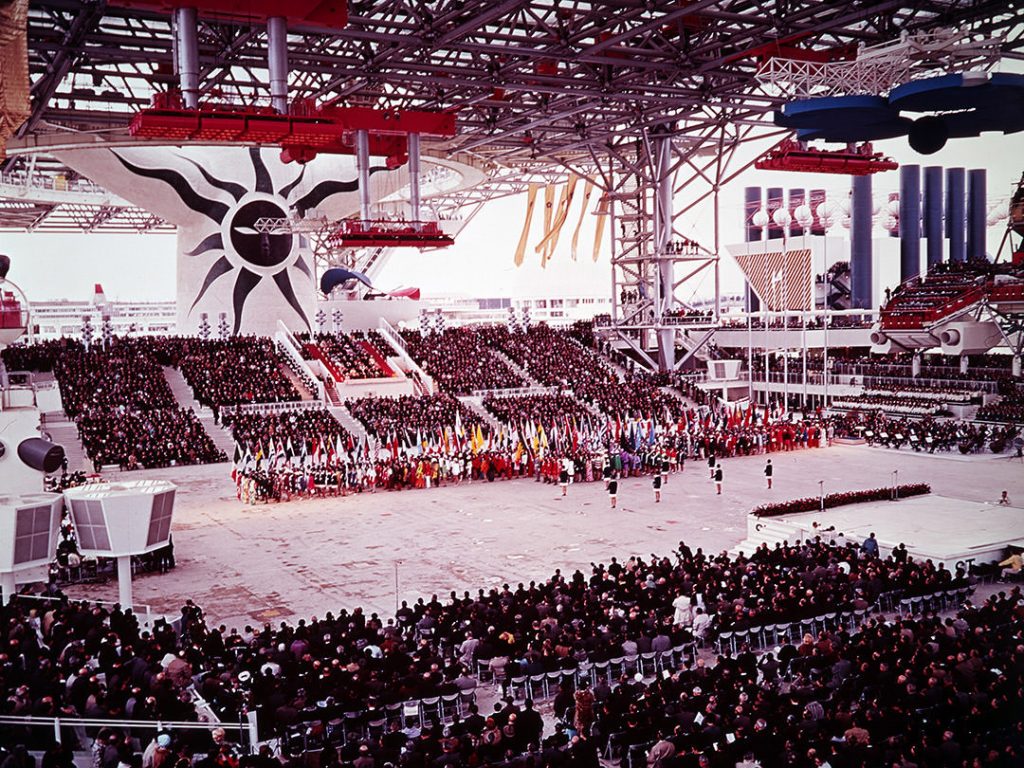

‘Konnichi wa, konnichi wa, countries of the world, konnichi wa.’ In 1970 the words of Minami Haruo rang out, welcoming the citizens of the world to the largest event ever held in Osaka: Expo 70.

Thirty years ago, at the end of the Mido-suji line in what is now a rather odd park with a couple of dilapidated towers, the world came to witness an event that put an indelible mark on Osaka, and Osaka on the world map.

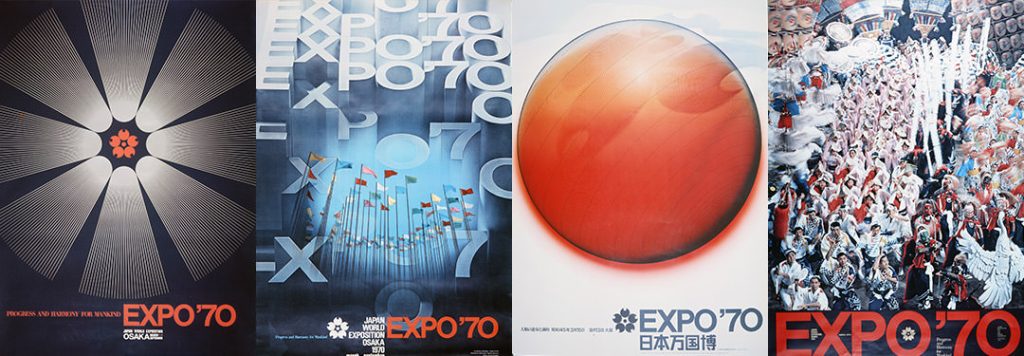

Japan had planned to hold an Expo in 1940 to commemorate the 2,600th year of the ascension of the first emperor. These plans were curtailed by the war with China and when the event did arrive, the Theme Committee decided on ‘Progress and Harmony for Mankind’ as the central theme. In a time of early space exploration, technology was seen as the way this would be achieved.

World-renowned science fiction writer, Komatsu Sakyo, was involved from the very beginning. ‘As this was the first exposition in Asia, we wanted to combine traditional Asian culture and crafts, such as art and weaving, with modern technology, such as space travel. This was a time when one billion people worldwide saw the Apollo moon landing on television, and one billion people in China didn’t.’

The planners decided that they would build a ‘glimpse of a future city’, at a cost of 200 billion yen, covering 3.3 million square metres in the Senri hills, 30km north of Osaka city. Komatsu described the site before construction as, ‘Horrible – just pine forests, bamboo groves and snakes.’

An estimate of 50 million visitors was made, and to transport them to the site a whole new infrastructure had to be built. Nine new expressways covering 80km were constructed and the Mido-suji line was extended 10km from Esaka to the site. ‘A large number’ of Osaka’s ‘traditional canals’ were filled with concrete to provide the space for the park and the new towns that followed. This went down well in the Komatsu household. ‘My wife and children said it was like a dream.’ A dream with a total cost of 1,000 billion yen.

To get the estimated 1 million visitors from overseas here, the official sponsor, JAL, added 2 jumbo jets, 9 DC-8s and 6 Convairs to its fleet, and offered flights to and from the US west coast at $614, landing at the specially built international terminal at the then Osaka (now Itami) airport.

The Expo site was divided into a northern zone containing the Japanese gardens and international pavilions, and a southern zone with Expoland, a recreational area including the ‘Daidarasaurus’, a 4,500-metre-long jet coaster, parking for 26,000 cars, branches of the world’s banks and about 100 computers. Both zones were connected by the 118,000 square metre Symbol Zone, the heart of Expo.

The Symbol Zone consisted of a rose garden, the Expo Museum of Fine Arts, Expo Hall, a floating stage, Festival Plaza, Expo Tower and the lasting symbol of Expo, the Tower of the Sun, representing ‘mankind challenging destiny.’ The plaza was covered by the world’s largest translucent roof, and here people could see films projected onto fountains, a priceless collection of the world’s masterpieces, including Renoir, Van Gogh and Picasso, giant robots Deme and Deku, performances by international and domestic stars like Marcel Marceau, the Royal Ballet, Ozawa Seiji, Leonard Bernstein, Sammy Davis Jr., the Bolshoi opera and the New York Philharmonic and the first ever IMAX film, ‘Tiger Child.’

In the northern zone, around 120 pavilions represented nations, states, provinces and private enterprise. Shaped to represent a cherry blossom, the Japanese pavilion, under the theme ‘Japan and the Japanese’, presented the ‘past and present of the land’ and the future ‘when the world will have come to know Japan better and the Japanese will have developed their dreams.’

Pavilions representing ideologically opposed nations combating the cold war jostled for superiority. The Americans presented ‘Images of America’ and had the largest air-supported roof ever built. The USSR, honouring the centenary of the birth of Lenin with the theme, ‘Harmonious Development of the Individual under Socialism’, had the tallest building at almost 110 metres, topped in fine style with a 6-metre hammer and sickle.

More than 64 million people eventually came, making the future city a busy one. Queues formed everywhere, particularly at the American pavilion, where most people, not even Komatsu, didn’t get to see the most popular exhibit, a moon rock retrieved by Apollo 11. ‘I only saw people’s backs.’

Marine Noel Brewer, then stationed near Yokohama, had a similar experience. ‘I took the bullet train to Expo 70 three times. I didn’t go into the major pavilions, since the lines were too long, but I wandered around taking photos and sampling different foods.’

Viking dishes at the Scandinavian pavilion, pheasant from Czechoslovakia, Munich beer and French escargot gave many their first taste of international cuisine, and the image of lamb as a post-war tinned meat was banished as they devoured delicious lamb curry.

The future city was cooled by the globe’s biggest air-conditioning plant and watered by 30,000 metres of pipes carrying 6,000 tons of water per hour. Its citizens travelled by monorail, a 3.35 km ‘Moving-Walk’ of plastic tubes shuttling 10,000 people around the site at a speed of 40m/min, the ‘Ropeway’, gondolas transporting 15 people 30m above the ground from the east to west gate in 7 minutes and were guided by a host of Expo hostesses, the ‘Flowers’, ‘Sisters’, ‘Angels’ and ‘Lost Children’s Friends’, 233 ‘pretty women in striking uniforms’ selected from all over Japan and Okinawa.

Admission was from 100 to 800 yen, and to avoid the queues special ‘courses’ were laid on. The ‘Women’s course’ gave a tour of ‘treats’ such as the French, Wacaol-Riicar, Gas and Textiles pavilions, a look at the Takara ‘Beautilion’ and fashion shows and jewellery displays. The architecture and image course concentrated on films, lasers and smoke screens, while the ‘Total Experience’ course offered ‘breath-taking’ displays provided by Pepsi, Hitachi and Fuji and a ride on the Daidarasaurus.

The impressions on the visitors and the effect on the area were, according to Komatsu, lasting. ‘Expo fired a shopping fever. Some housewives said it was very exciting; a showroom of worldwide department stores. There were so many toys, carpets and decorations from outside Japan. So many conservative people tried exotic drinks and started using exotic spices. Afterwards they tried to visit foreign countries and many Osakans [trying] to organize a huge party including foreign people recognized that cultural exchange was very important.’

Part of that cultural exchange was experienced by Brewer. ‘I met some young ladies, but they couldn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Japanese. We went into the Italian pavilion where we found a Japanese lady who spoke Italian, and an Italian lady who spoke English. My new friends spoke Japanese, which was translated into Italian, which was translated into English.’

The Expo ran from March 15th to September 13th. On the first day, Komatsu recalls, it snowed. ‘The workers from Africa shivered and said, “What’s that?” It was their first experience.’

Within six months of the last day, most of the site had been pulled down, but the many first experiences lingered. ‘After Expo 70 a very rude and old-fashioned resistance to development lessened and everyone recognized the importance of a new international airport. There was a big impact, it was very exciting.[Beforehand] nobody knew Osaka at all. Now they do.’

This article was first published in Kansai Time Out, May 2000.

Illustrations from here: https://taiyounotou-expo70.jp/en/about/expo70/